by Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel

The practices of slavery and colonisation in Africa, amongst others, contributed significantly to disorienting people’s indigenous identity by eroding religious practices, forms of education, governance structure, artistic and social cultures. However, in as much as these practices scarred indigenous lifestyles, cross-cultural adaptation is not totally negative since cultural shoulder-rubbing contributes to hybrid personalities, social-cultural and global development. Many cultures of the world recognise the enormous benefit of multicultural interactions and in Africa, for example, the Akan of Ghana say Ekyinekyin ye sen enyinenyin, which literally translates as “Travelling widely is better than longevity with no travels.” The underlying philosophy in this proverb is that welcoming and interacting with different cultures come with enormous benefits including fostering intercultural learning and understanding, peace building and respect for one another. For this and other important reasons, the peoples of Africa are generally embodied with a high sense of hospitality, opening up to people of different cultural backgrounds in and outside the continent.

Contrary to the African hospitality, the colonialists who experienced African cultures nurtured and harboured negative perceptions which featured in their writings about Africa in precolonial, colonial, postcolonial, contemporary, and even present times. Consequently, their idea remained to superimpose their ideas, and aesthetic ideals and beauty culture standards on Africa. Their writings documented African art, religion, social, cultural and aesthetic ideals as ‘to reinforce the picture of African society as something grotesque, as a curious, mysterious human backwater, which helped to retard social progress in Africa and to prolong colonial domination over its peoples’ (Nkrumah, 1963, p. 2). For example, African art was relegated to craft and labelled as ethnic, primitive, fetishist, idolatrous and mundane and presented as such in European museums.

In addition, the diverse fashion found in Africa was referred to as costumes, a term perpetuated in current scholarship. Fashion has been rigidly compartmentalised into West versus non-West, tradition modern versus, and fashion versus dress (Jansen & Craik, 2016; Rabine, 2002). Fashion from Europe and North America is Western fashion perceived by the colonialists as modern and proper while the Non-Western fashion refers to fashion beyond Europe and North America. Africa includes the non-West fashion (Jansen, 2021; Welters & Lillethun, 2018). The neo-colonialists’ self-aggrandising assumption asserts fashion as a Western phenomenon and that fashion outside Europe and North America is recent and a result of globalisation. This position does not acknowledge different fashion systems that were in existence before colonialists’ invasion and evolving fashion systems in Africa and other parts of the world. Again, assigning binary descriptors such as tradition, dress, and costume to African fashion means that it is unchanging, and symbolic and not disconnected from its cultural context in terms of significance and uses. Due to these political binary and apperceptions, the concept of decolonisation is necessary by rewriting these forms of ‘intellectual’ dishonesty of social and mental domination on the peoples of Africa. ‘It is impossible to respect an intellectual unless he [/ she] shows … kind of honesty. After all Academic Freedom must serve all legitimate ends, and not a particular end’ (Nkrumah, 1963, p.4). To Nkrumah, academic freedom should not be used to ‘cover up academic deficiencies and indiscipline.’

The decolonisation conversation and agendas remain constant as conscious efforts by civil societies and academics to deepen the decolonisation discourse effects felt also on people’s identity and ideology. In the past two decades, there have been more compelling decolonial efforts in the field of fashion and textiles. The following: India Collective, Centre for Research of Fashion and Clothing, Fashion Liberation Collective of North Africa, African Fashion Research Institute, and Research Collective for Decoloniality and Fashion feature prominently in fashion decolonial discourses through research.

Against this background, fashion decolonisation efforts reposition the non-West fashion including African fashion art and history into its proper context, detailing its creative contributions to the fashion world. These research collectives address the sensitivity of rewriting the wrongs, fabrications and misassumptions of African fashion contribute to fashion inclusivity on many levels.

One glaring example is the issue of the term classic in the context of fashion. The term classic refers to a relatively long-established and popular form or style of dress. The suit, usually a three-piece ensemble consisting of a jacket, trouser and shirt, is a classic in Western dress code and has been in existence for centuries. Occasional changes in structure of the suit manifest in the lapel size, notch position, cuff, button placement, length, cut, fit, fabric type and texture, colour and decorative stitch and other enhancements registered on it, yet, it is not perceived as a costume, but as a fashionable dress. In the case of Africa and West Africa, to be specific, there are several classic wraparound fashion such as the breast and waist covers (Figure 1), toga (Figure 2), kaba and slit (Figure 3), smock fashion and tunics. These African classics keep changing in design, fabric use and texture, cut, fit and colour just as in the case of the suit.

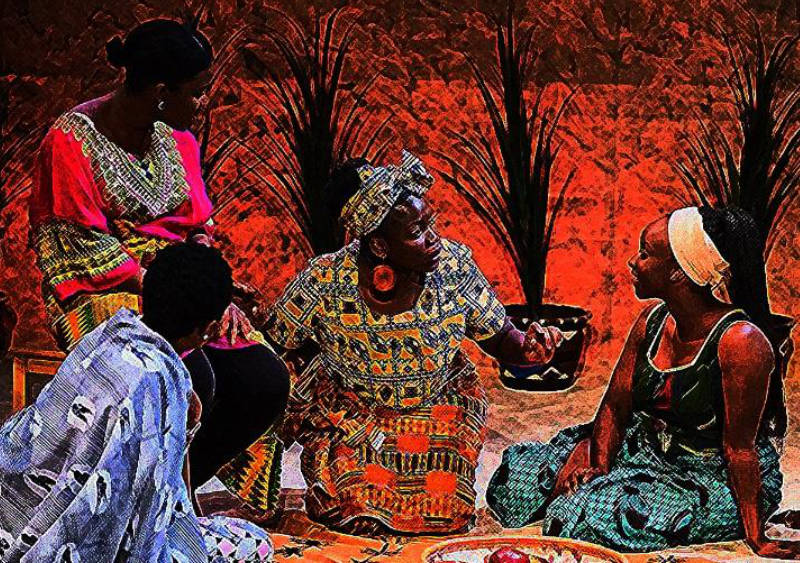

Fig 1: Dum Emmanuel Tettey: Our Women Our Culture, 2021

Wearing of breast and waist covers (Figure 1) flatter the skin with young feelings as it exposes the upper limbs, back the body, and the lower limbs as well as the navel regions. It is usually worn by young females, and has influenced many body grabbing designs that are usually bare-chested. The weather conditions in Ghana makes this classic comfortable to wear.

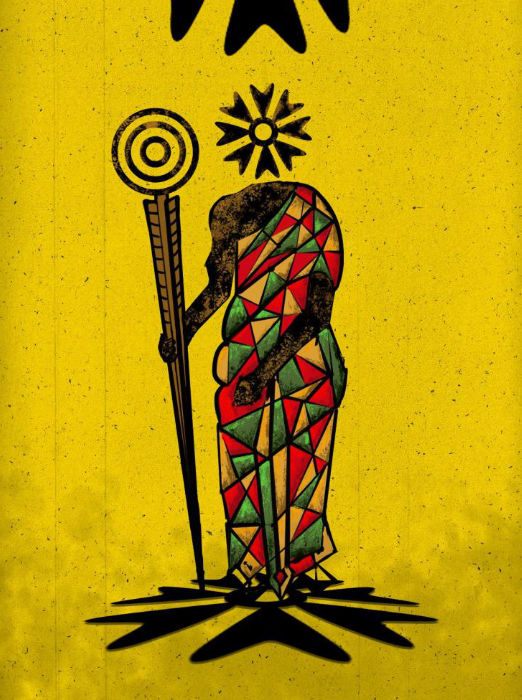

Fig 2: Betty Yaa Addo: The Linguist, 2021

In figure 2, the artist depicts a tapestry of colourful triangular shapes wrapped around a seemingly human figure holding what appears to be a linguist staff. The wraparound colourful triangular designs give an impression of toga style of wearing fabrics. Toga remains a major masculine classic in contemporary Ghana. However, Western academics and scholars continue to refer to these African classics as costumes or tradition dress. The consequence is that in the academic fashion world, these terms denote an unchanging dress and something that is anti-fashion. These types of bias against African fashion continue to be contested by academics who persevere with African decolonisation conversations.

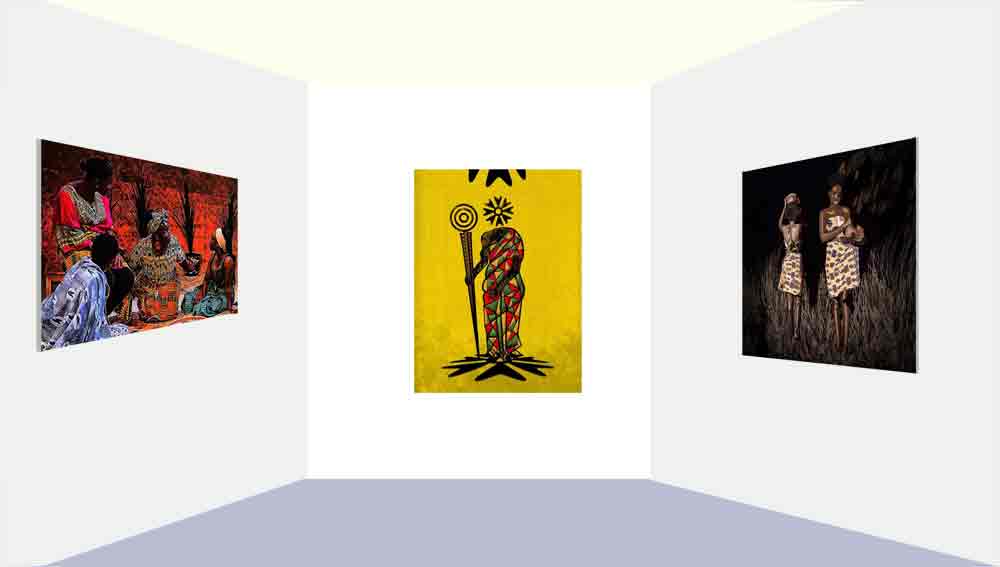

Fig 3: Adzato Miriam Mawunyo: Storytelling, 2021

Kaba and slit (Figure 3), a three-piece ensemble and feminine wear consisting of a blouse-like top, usually long skirt and large cover cloth, had undergone varied stylisations, cut, fabric texture and colour changes. New designs of this classic trickle onto the market from time to time as it is a formal wear for females in many parts of West Africa and is considered a classic in Africa. In this artwork (Figure 3), the centrally placed human figure in a kneeling position as well as the figure in the top left wear kaba and slit as they dramatise storytelling moments that characterised precolonial and postcolonial Ghana. Perhaps, the artist's presentation is a recast of past times in terms of storytelling and way of life. The presentation of the garments of the figures reflects her cultural mores.

In this exhibition three of the artists’ (Dum Emmanuel, Betty Yaa Addo and Adzato Miriam Mawunyo) works indirectly reflect the prevalent fashion in their respective communities that give them a sense of collective memory. Though, their intention might not be showcasing their classics, but their way of clothing their human figures reveal what pertains in the Ghanaian fashion culture.

Attempts to gather images and interpret them for their inherent collective memory based on their educational relevance, reignite the discourse of decolonisation. That is to say that, collecting images into a transnational portal for the purpose of fleshing out their collective memory for teaching and learning is one way of challenging and disrupting the misassumptions and apperception about non-West fashion for global good. The attempts of collecting images from different countries for the sole purpose of finding their educational relevancies has the tendency of helping decolonise curricula of nations who have genuine interest in learning from other nations. The process informs multinational and continental engagements that gradually water down, if not erase, the hegemonic posturing thereby resulting in producing academically honest intellectuals and global citizens.

References

- Jansen, M. A. (2021). Foreward. In Sarah Cheang, Erica De Greef & Takagi Yoko (Eds.), Rethinking Fashion Globalization (pp. xvi – xvii). Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Jansen, M. A. & Craik, J. (Eds.). (2016). Introduction. In Modern Fashion Traditions: Negotiating Tradition and Modernity Through Fashion (pp. 1 – 24). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Nkrumah, K. (1963). “The African genius.” Speech delivered by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame. Nkrumah, President of the Republic of Ghana, at the opening of the Institute of African Studies on 25th October, 1963.

- Rabine, L. (2002). The global circulation of African fashion. Berg.

- Welters, L. & Lillethun, A. (2018). Fashion history: A global view. Bloomsbury Academic.