Transcultural Perspectives on ´Gender` between the Global South and the Global North

By Bea Lundt

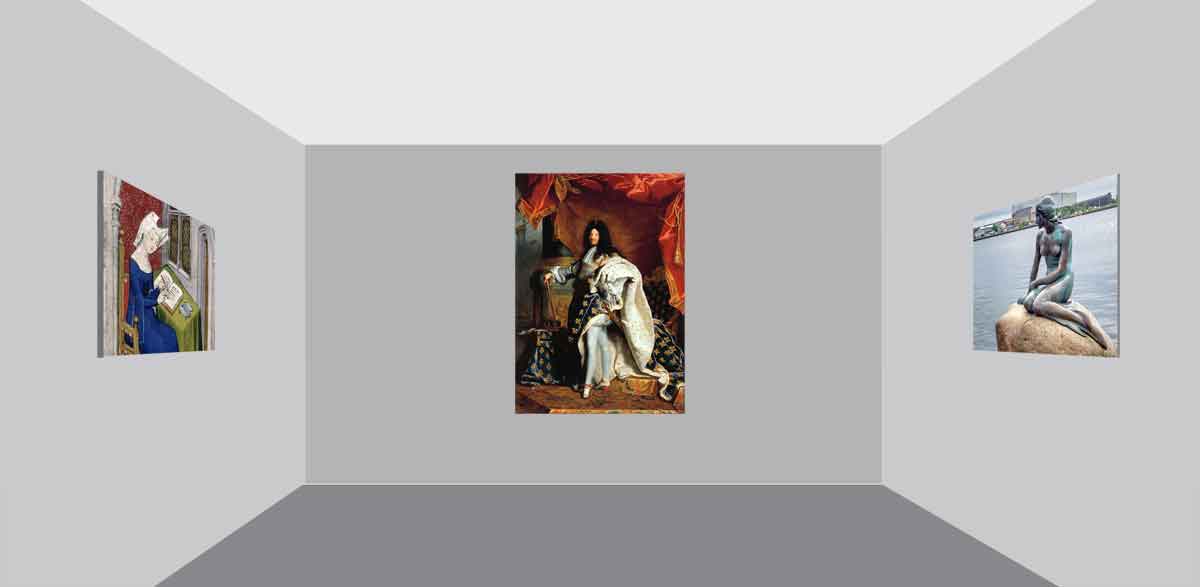

- Making women visible: Paintings showing Christine de Pizan, an independent woman and creative writer of the 15th century in Europe

- Deconstructing masculinities and male power in European History: A famous portrait of the French King Louis XIV from the 17/18th century.

- Decoding a mythic figure as part of the symbolic order: A statue and paintings of the figure of a mermaid 19/20th century.

Introduction

We speak of gender when it comes to the question of which examples from visual culture should be shown and utilised in school classrooms as well as in public spaces in order to fulfil the current demands for inclusion, equality, and sustainability in global cooperation (UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, Goals 4 and 5).

Men have traditionally defined the selection of works of cultural self-representation in countries of the so-called Western world (Heinrich August Winkler), determining the conditions for the production and reception of such objects. Certain ideas of male creativity, a corresponding cult of genius, and a structural anchoring and organizational execution of these ideas among the so-called ‘avant-garde’ have dominated since the middle of the 18th century. The selection of works considered valuable has thus occured at the exclusion of other criteria and people (Söll in Kortendiek).

By looking at visual culture through the lens of gender, we can identify the steps needed to reassess this selection of works on the basis of cultural multiplicity (Ernst Wagner). First, we need to re-evaluate traditional female activities and creative achievements in visual culture and make them (more) visible. Concurrently, we need to demystify and deconstruct the ideology of heroic masculinity. We still need to rethink and discuss those images of gender that are circulated as part of the art historical canon and have influenced the views and ideas of a broad public. (I have provided examples for each of these three points).

In order to achieve a lasting reorientation, it is also important to ‘question the premises’ (Söll, p. 609), under which this marginalization of femininity has taken place. Only when we understand the societal causes underlying these structural inequalities and injustices can we begin to fulfill the 2030 Agenda. We need initiatives for a gender-equitable, inclusive production and gender-sensitive reception of visual culture in the future.

What is ‘Gender’? Definitions in ‘Western’ Gender Research

‘Gender’ is a central category for differentiating between humans. Traditionally, people are assigned to one of two groups based on their biological sex: male and female. Many other characteristics are used to categorize individuals and groups: age, social and regional origin, class, (socioeconomic) status, ethnicity, religion or spiritual community, physical and psychological state, and sexual orientation. In addition, all these factors operate within the dimensions of space and time (‘entangled history’). Within this broad spectrum, we can develop a field of knowledge on the variety of human life with numerous relationships, networks, overlaps, and connections. This observation of gender within the interplay of various criteria is called ‘intersectionality’. Ideas of what is considered typical or even ideal for one biological sex or the other differs across time and culture, revealing the social constructions of ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’ (various articles in Kortendiek et al.). These characteristics are often consolidated into concrete patterns that can become socially dominant. The Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell describes images of masculinity in the modern period and defines one of them as ‘hegemonic’ in the power discourse with respect to other, concurrently existing types of masculinity.

Eliminating Gender Polarities: ´Gender` in the ‘Western world’ Amidst the Challenges of Globalization

In the last several decades, ideas about gender in the so-called ‘Western world’ have significantly changed. Since the end of the 18th century, certain ideas of a natural, or biologically determined and, therefore immutable, polar dichotomy of characteristics of the two sexes have served as a model, particularly for the middle class. Traditionally, men fulfilled their role in the ‘public’ spheres of life, whereas women fulfilled their role in domestic or ‘private’ spaces. This binary structure was laid out hierarchically, whereby the role of the female was subordinate to that of the male (Opitz). Thinking in dualisms, characteristic of modern imperialist nation states in Europe and other regions considered part of the ‘Global North’, took on a form that was based on the idea of unity within stable, closed borders: unity of folk, religion, culture, and language. This concept defined the ‘native’ and legitimized the marginalization of individuals and groups considered ‘foreign’; it encouraged racism and wars and erupted in excesses of violence during this extreme century (Wolfgang Reinhard).

This concept of ‘modernity’ has been criticized (e.g. by post-colonial groups and the sustainability movement), not only for its unscrupulous and unjust growth model, but also for its essentialist ideas about gender. In international declarations like the 2030 Agenda, the member states of the international community have pledged to abandon the dichotomous model of European modernity as an ideal and point of reference against which other regions should measure themselves. Just as each county falls short in meeting the newly defined sustainability goals, the same is true with regards to gender equality (2030 Agenda, Goal 5).

The assumption of a dual gender structure, which is central to the believe that the world is comprised of opposites, has been refuted by various declarations made at both the German national and international level. An awareness of the diverse ways gender manifests, has expanded and pluralized the previous gender binary. Consequently, in 2019, Germany created a third gender category (‘diverse’), wich can be used to identify oneself on official documents.

While gender concepts in the West are often precipitately understood to be universally valid, this paradigm shift brings with it a new openness for a further loosening of previously rigid ideas about gender. We must ask, in the course of globalization, what ideas about differences between people have developed in the ‘Global South’ and what practices shape the everyday lives of men and women there? Answers to such questions expand our knowledge of the variety of global visual offerings, but they also demand reflection on previous catalogues as a prerequisite for the necessary correction of archaic images and prejudicial stereotypes. In so doing, we can prepare avenues of cooperation through transcultural dialogue.

Gender is Variety: Criticism From African Scholars of ‘Western’ Gender Discourse

Scholars from the ‘global South’ (e.g. from different African countries), have repeatedly criticized ‘Gender Studies’ for being biased on a unilateral concept of gender developed in only valid for Western modernity (Oyewumi, Kelly). In particular, they reject the performativity thesis of Judith Butler. This most influential American feminist assumes that gender is a linguistic and, therefore, variable convention that results from certain powerful interests in a heterosexual social order. African scholars accuse her of presenting an unrealistic perspective in her attempt to de-biologize gender.

However, it is not only the central concept of ‘gender’ in the research that they criticize. The investigative horizon and casting of the problems, the focus on certain regions (metropolitan areas) and social groups (the middle class and the elite), as well as the research techniques, are said to be Eurocentric since they originate in the scientific cultures and traditions of the Western world, e.g. in its fixation on written sources at the neglect of other forms of expression and the performative handling of narratives.

This puts into question the validity of the entire area of ‘gender studies’. However, this criticism extends far beyond an internal research controversy. Rather, it is frequently expressed in the political arena and directed against the self-image of the so-called ‘Western world’ and the corresponding definition of ‘us’ and ‘them’, whereby the latter, measured against ‘Western’ norms, is considered deficient. This condescending view of gender relations in Africa has been used to legitimize paternalist, neocolonial actions that have affected many areas of life, e.g. formal education.

African scholars argue that before the colonial period, no corresponding dual gender structures existed in their countries but rather a permeable, fluid one. ‘Gender’ had never been an essential criterion for differentiating between persons until European invaders imposed their normative order of separating people according to biological sex into different spheres of life. Consequently, jobs held by women were given to men and women were relegated to the domestic sphere. In addition, many men were ripped from their families and used for forced labor, e.g. road construction, in distant areas. Traditional forms of cohabitation, e.g. polygamy and matriliny, were discredited. At the same time, the colonial masters unscrupulously fulfilled their own sexual desires: abuse, rape, and mistreatment were daily occurrences. The colonial masters seldom took responsibility for the children they sired. Today, postcolonial Africa is characterized by a great degree of hybridity, reflecting the integration and perpetuation of imposed gender structures as well as the re-establishment of precolonial patterns of cohabitation (Kam Kah, Cole et al., Ampofo). Because gender is a structure shaped by culture and is deeply embedded in everyday life, it presents valuable opportunity for confronting colonial history.

In such transcultural gender discourse, we must additionally recognize the value of oral traditions and acknowledge the theft of written records and material objects by the colonial masters from these now-independent countries, attention that has not been found in the global discourse until now (Sarr, Savoy).

Tasks and Perspectives

There is no question that we must dismantle dominant Western discourse in research environment and in everyday gender culture (and elsewhere). Within the ‘Western world’, the dissolution of gender polarities and an acceptance of a spectrum of gender identities — in which individuals can assume any role regardless of biological sex — represents a convergence of concepts (Kam Kah, Lundt). This presents an opportunity for dialogue and exchange. The field of visual culture provides an apt lens through which to examine this convergence since it centers visual, as opposed to written, forms of expression.

Interpersonal exchanges in our partner countries allow us to better understand the contextual and functional significance of ‘local knowledge,’ an understanding essential for cooperation. In the process, we should reflect on other perspectives. The two worlds do not encounter each other in isolation but rather have influenced one another in various ways for centuries (‘entangled history’), e.g. through hybrid population structures as well as groups in the diaspora.

Translated by Kelly Thompson

Literature

- Akosua Adomako Ampofo: Gender and Society in Africa. An Introduction. In: Takyiwaa Manuh, Esi Sutherland-Addy (eds.): Africa in Contemporary Perspective. A Textbook for Undergraduate Students, Accra 2013, pp. 94-115.

- Judith Butler: Gender Trouble, Routledge Classics 2006.

- Catherine M. Cole, Takyiwaa Manuh, and Stephan F. Miescher (eds.): Africa after Gender, Indiana University Press 2007.

- Raewyn Connell: Gender in World Perspective (Polity Short Introductions), 4th edition 2020 (first published in 2014).

- Anke Graneß, Martina Kopf, Magdalena Kraus: Feministische Theorie aus Afrika, Asien und Lateinamerika, Stuttgart 2019.

- Henry Kam Kah: The Sacred Forest. Gender and Matriliny in the Laimbwe History (Cameroon), c. 1750-2001, Berlin 2015.

- Ibid. and Bea Lundt (eds.): Polygamous Ways of Life Past and Present in Africa and Europe, Zürich 2020.

- Natasha A. Kelly (ed.): Schwarzer Feminismus Grundlagentexte, Münster 2019.

- Bea Lundt: Geschlechtergeschichte an einer Hochschule in Ghana (Westafrika). In: Anna Becker, Almut Höfert, et al. (eds.): Körper-Macht-Geschlecht (commemorative publication for Claudia Opitz.), Frankfurt/ New York 2020, pp. 123-134 (in print).

- Oyeronké Oyewumi: Colonizing Bodies and Minds. Gender and Colonialism. In: ibid (ed.): Invention of Women. Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses, Minneapolis 1997, pp. 121-156.

- Claudia Opitz-Belakhal: Geschlechtergeschichte (Historische Einführungen, 2010, 2nd edition 2018, 3rd edition 2020, Campus Verlag.

- Wolfgang Reinhard: Empires and Encounters 1350-1750, Harvard University Press 2015.

- Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy: Zurückgeben. Über die Restitution afrikanischer Kulturgüte, Berlin 2019. Translated from the French.

- Anne Söll: Kunstwissenschaft und Bildende Künste: von männlicher Dominanz, feministischen Interventionen und queeren Perspektiven in der Visuellen Kultur. In: Beate Kortendiek et al. (eds.): Handbuch Interdisziplinäre Geschlechterforschung, 2 vols., Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden 2019, vol. 1, pp. 609-618.

- United Nations: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (a.k.a. the 2030 Agenda), https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. Accessed on 6 September 2020.

- Ernst Wagner: Welche Kunstgeschichte sollen wir betreiben? Content im Horizont der Globalisierung. Auf dem Weg zu einer transformativen Kunstpädagogik. In: Kirschenmann, Johannes & Schulz, Frank (Hrsg.), Begegnungen - Band 2 der Sonderreihe KUNST · GESCHICHTE · UNTERRICHT. München (Kopaed). 2021. S. 270 – 310

- Heinrich August Winkler: The Age of Catastrophe: A History of the West 1914-1945, Yale University Press 2015.