I argue in the following text from a special position. Firstly, I was present in Bayreuth on 26.4.2022 when the two co-authors, Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel and Mahmoud Malik Saako, discussed the painting in a larger circle. The representatives of the Iwalewa House clearly expressed their doubts about the (traditional) title of the painting "Christ".[1] Perhaps this brought the question of who was depicted in the painting, Christ or another person, to the fore. This question also shapes my discussion of the painting presented here. It became the guiding theme behind which other topics disappeared, such as the question of the painting's function (what was it created for?), its biography (how did it come to Bayreuth?) the role of oil painting (is it a European import), the context of the debates on modern art during the independence movements in Africa (does the painting belong to a global modernism after the Second World War or does it mark a Nigerian path? [2]) - to name just a few.

My own interpretation is therefore less an independent approach to the work than a response to the positions presented with the intention of building bridges between the approaches by introducing a meta-level. Whether this is convincing, whether the bridge is sustainable, is for the reader to decide. But more on that below.

Traps through aesthetic stereotypes that lead to false classifications / interpretations

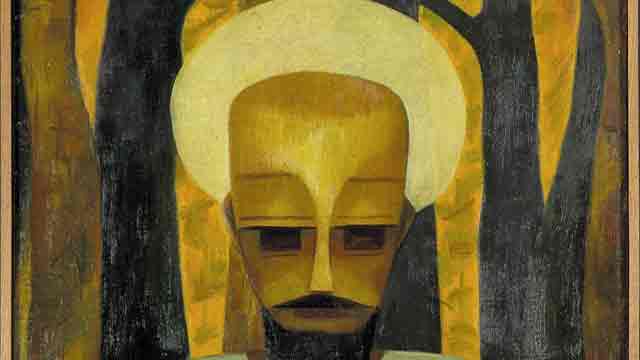

And a second preliminary remark: I didn't like this picture at the beginning. It reminded me too much of the religious pictures of the 1950/60s of my childhood. They were popular for death pictures back then: A mixture of a bit of Pre-Raphaelite and icon-inspired imagery, soaked in the formal world of a moderate and esoterically inclined modernism (Franz Marc). The intention was easy to see through: To somehow keep alive that which, in my view, was no longer contemporary at all, and to do so through a bland, unconvincing and even less convincing adaptation (a kind of "modern facing"). This is also why, when I saw the picture hanging at the entrance to the Iwalewa House from the corner of my eye, I immediately saw a Christ.

Iconography - inclusion of other perspectives

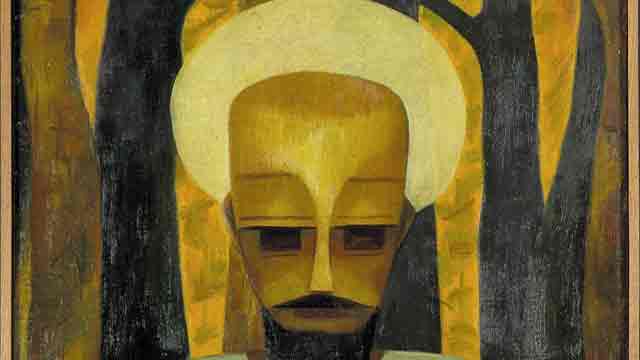

Detail

In the discussion mentioned at the beginning, the intervention of Mahmoud Malik Saako was really surprising for me - against the background of this perception, which was shaped by my own stereotypes. The halo (which I saw - see detail) was a turban (which Malik saw). But I could not counter his view. There was no argument for the interpretation as a halo. This is also true now when I read Malik's text (like Osuanyi's). So I first had to recognise my stereotype in perception, which had lured me onto a perhaps (?) wrong track, I had to get rid of this, unlearn something, in order to be able to open up to the other perspective.

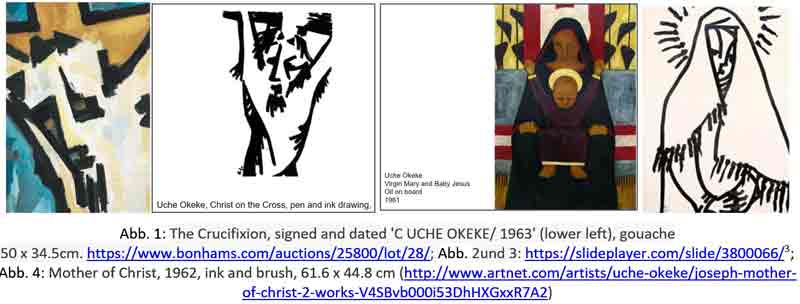

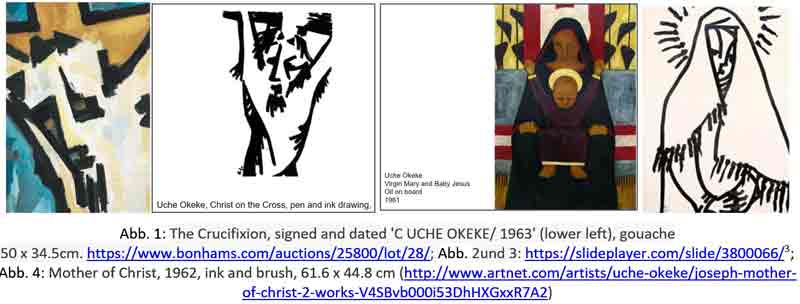

Why I - retrospectively - still speak of "perhaps wrong", a research on Okeke's work has confirmed as meaningful. After all, there are obviously works in his oeuvre that iconographically quite certainly represent Christ or St Mary, as an internet search reveals (see fig. below). The auction house Bonhams (Abb.1) states - even if for 1963, two years after our work: "in 1963 ... the Passion of Christ was a recurring theme for the artist. He had produced the stained-glass designs of the Fourteen Stations of the Cross in Munich earlier in the year." (www.bonhams.com/auctions/25800/lot/28 accessed 14 Sept 2024)

Christian motifs in Uche Okeke's Ouevre between 1962 and 1963 found by the author on the internet (May 22, 2022)

Perhaps this is why the discussion about whether Christ or a Muslim is depicted makes me feel uneasy. In my mind, the question is connected with the attributions or depreciations: To whom / which faith does the work of art belong? Does it belong to the Christians, the Muslims, or the traditional believers in northern Nigeria, if, as Philipp Schramm or Mahmoud Malik Saako suggest, one also discovers a traditional wooden mask?

New approach and reflection on its anchoring

Hence my attempt to think of the painting in a different way, i.e. not from the artist's point of view and what he or she wanted to represent. In doing so, it is clear to me that I am taking a specifically Western approach to a modernist work (where I now place Okeke's painting) with my new approach. This approach is based on the loss of a binding iconography and a fundamental openness / never-quite-unambiguity of 'autonomous' works of art for a Western-oriented, middle-class audience. In addition, my proposal for interpretation is based on a specific position in the interpretation of images, from production theory to reception theory (in the context of constructivist epistemology). The loss of a binding iconography is accompanied by a greater significance of form (which is now itself charged with content to compensate for the loss). In a next step, I therefore try to examine the image - beyond a positioning in the question of whether it is an "Islamic" or a "Christian image" or a "traditional image" - form-analytically.

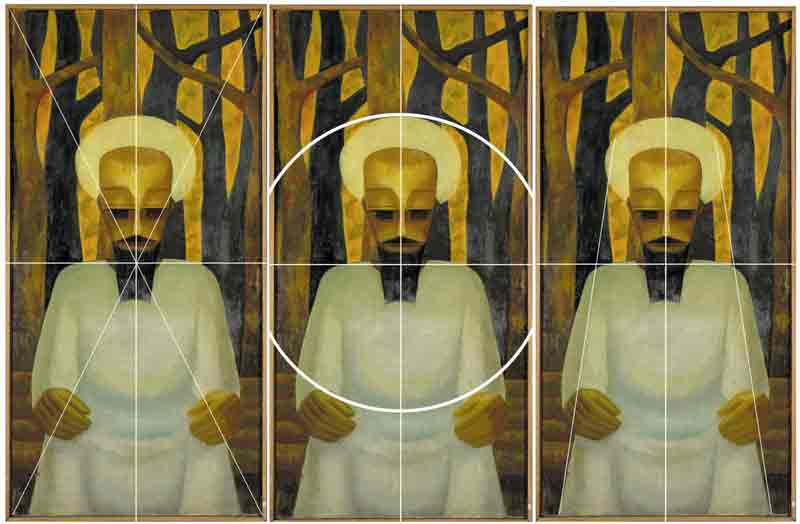

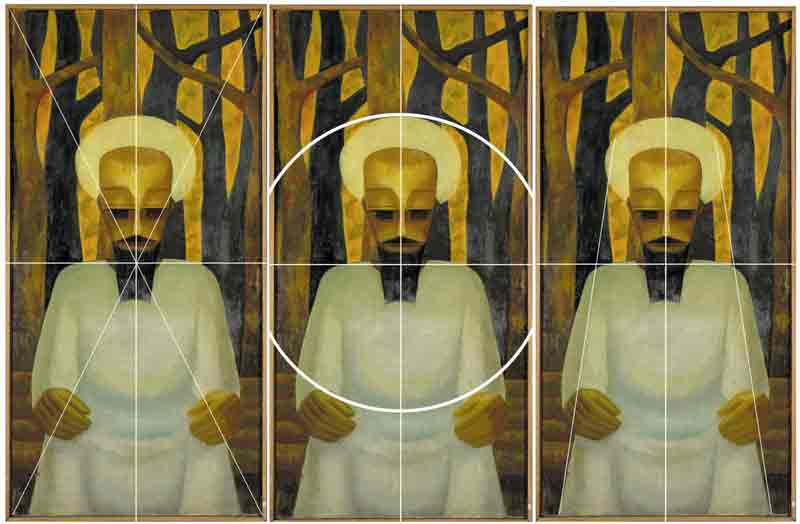

Analytical composition with auxiliary lines. (c) the author

Form analysis

The dominant, almost penetrating axial symmetry in a very high longitudinal format speaks of high order; the pyramidal structure of the figure also speaks of calm and stability, indeed of sublimity and dignity, of quiet, immovable power. And this dignity is not fed by external insignia or theatrical staging, but by a calm that radiates from within. It is a picture in front of which one can become calm if one trusts the order as a viewer.

The striking human figure contributes to this effect. Although clearly figurative, it does not represent - to the degree of abstraction - a concrete portrait or a human being that can be grasped by the senses. This is most obvious in the geometricised eye area, which is shaded in various dark zones. This makes the gaze ambiguous: is the figure looking at the viewer, is it looking forward, is it looking inwards (contemplatively, with closed eyes)? Together with the geometric rhythm of the picture's surface (the symmetry, but of course above all the parallels that can denote eyelid, tear sac, eyebrow - or not) support the depiction of a human being in an abstracted ideal form that remains open to itself, as in a mask. The latter is also characterised by the fact that the viewer immediately sees what has been made, what has been assembled, as in the case of the moustache, for example.

The figure sits quite classically in front of a middle and a background: at the bottom the zone (again - between two-dimensional and spatial effect - strongly abstracted) is divided into horizontal stripes, which become slightly narrower towards the top. They again suggest something familiar (a wooden bench), but this remains ambiguous. In the upper zones, the tree trunks (without leaves) form the liveliest, least symmetrical, most restless element in the painting, even if the alternation of light and dark again shows the abstracting hand of the artist.

With this spatial layering in clear zones (background, trees, seat, figure), but also the geometric reduction of the forms, the picture looks like a carved relief. The colouring also fits in with this, for example when the "sky" behind the trees as well as the lighter trees have the same colouring as the face, while the beard, eyes and the dark trees form a second colour zone. The lightest zones are formed by the robe and the shape around the head. Despite the large spectrum in the area of light-dark contrast, the picture does not appear colourful, rather like a natural wood relief. An effect that is again particularly evident in one detail: the way the hands are shaped is reminiscent of hands carved out of a piece of wood.

This character is supported by the way Okeke uses oil painting. He clearly outlines the contours of the surfaces. The objects are each assigned a main colour, applied impasto with broad brushstrokes. The modelling creates plasticity, lightly set with internal structures enliven the colour surfaces.

Conclusion

The degree of abstraction, the modelling construction of the figurative out of a colourfulness, the strict symmetry of the composition, the tectonics of the pictorial space unfold a tableau that nevertheless - and this is now decisive - creates zones of ambiguity in the figurative. The viewer must fill these with his or her own ideas. The viewer's gaze is directed towards the picture, but the eyes do not look back. In this respect, the painting is suitable for contemplation, meditation, spiritual experience. In seeing the painting, one's own can come to rest. And so the distinction between the Christian halo, the Muslim turban and the ritual mask can also come to rest in the contemplation of the painting.

This consideration is based on an 'ideal viewer' of the work, i.e. it is reception-aesthetically oriented. If one finally turns it once again to production aesthetics, one could interpret the work as an attempt by the artist in which it experimentally unfolds what a spirituality beyond the distinction traditional - Christian - Muslim could look like.

Footnotes

[1] Philipp Schramm's position becomes clear in his text (https://www.bayfink.uni-bayreuth.de/de/Sommerausstellung-2021_-Not-yet/audio-not-yet---welcome/index.html).

[2] Perrin Lathrop, "Uche Okeke," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed May 21, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/uche-okeke/.