Administrative, esoteric and patriotic purposes until the first half of the 19th century

After an initial sighting the clothing can still prove to be expectable in the context of its time and regionality. While the medieval weapon seems useful for the guard's task, the hat's purpose can be seriously doubted. But peculiar as the outfit might be, it must have identified its possible former wearer as a civil servant, who was authorized, e.g. to punish violations of the rules. To protect the vineyard, a Saltner had to be reliable, vigilant, fearless, persuasive and loud. In addition to this executive function, there was also an esoteric one: Myths have developed claiming that a Saltner is able to defend himself successfully not only against thieves and ravenous animals, but also against attacks from the otherworld. Thus, the formerly more modest hat might have taken on a fetish-like function as well, alongside an expectedly Christian context — similar to the magic „Hexenkreuz“ (a shoe-length iron forged in the shape of a cross, von Hörmann 1872, p. 41-47) which should be part of the equipment of a Saltner too.

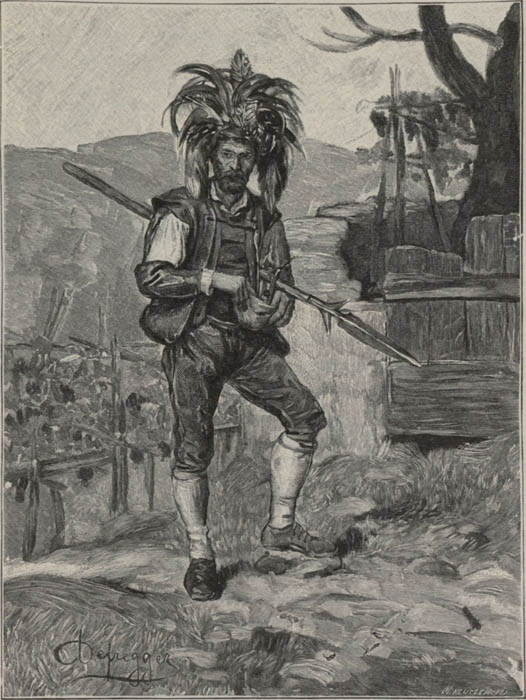

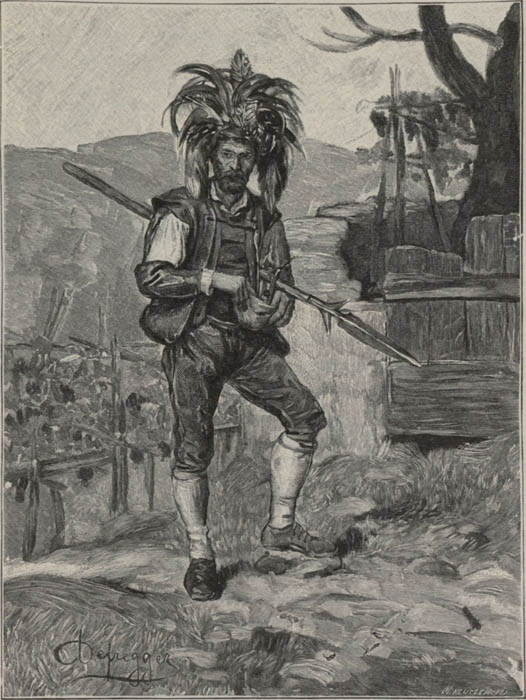

Fig. 1, 2: Meraner Saltner, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1875/1899 © Germanisches Nationalmuseum

In addition, there are other striking features of the costume. Apart from the hat, many handed down costumes of vineyard keepers look very similar to that of an outstanding Tyrolean folk hero. As to the beard, most vineyard keepers on contemporary pictures also come very close to Andreas Hofer, the leader of the Tyrolean popular uprising of 1809 (fig. 3). Thus, two hero constructions could be woven into the image of these objects: the brave guardian with supernatural powers and the defiant folk hero who successfully defended his country against the Bavarian occupiers (at least for a short time).

Fig. 3: Franz Defregger: Andreas Hofer, 1894, oil on canvas, Tiroler Kaiserjägermuseum, Innsbruck (© CC-BY-4.0 CC)

Tourist purposes in the course of 19th century

A steady evolution of this appearance towards hypertrophic splendor (cf. Ramming 1997, p. 119) could be observed. Whom did the vineyard keepers want to impress? Did the scary outfit or its models also have the function of a lure, even a courtship dress? One could speculate a lot about this, as well as the question of the addressees and the success of this posing in the rural environment. Indeed, there were harsh rules that state how vineyard keepers had to behave towards women (cf. von Hörmann 1872). Like the myths of nocturnal seduction attempts by witches in the vineyard, they also point to the possibility of their transgression (Matscher 1933, p. 217). The clearest indications of courtship even in the sexual are found indirectly where the vineyard keepers discovered their tourist attractiveness in the later 19th century. Here it was not only a matter of inspiring the exoticism expected from the outside. The Saltner in the role of „Papageno“ (Halbritter 2005, p. 88) offered a masculine performance to a changing — even female — audience, too. And the public, frightened by the wild man in the vineyard, gladly paid for this thrill with the usual, officially regulated tax for trespassing — and then sent a postcard with a picture of such a strange imposing guy out into the world (op. cit. p. 88-104, fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Meraner Saltner. Postcard sent 1907. © CC-BY-4.0 austria-forum.org

Use in the attempt of nation building until after 1900

The emergence of traditional costumes in the 19th century was due to an increased interest in regional distinctiveness. The dependence on supra-regional trade, a corresponding desire for a special appearance and the burgeoning tourism in picturesque South Tyrol drove this development further. The purchase of the object by the GNM in 1899 was completely in line with the museum's historistic concept. Unique characteristics were to be collected to support the idea of nation-building in the German-speaking area which includes parts of South Tyrol (Austria till 1918, then Italy) too. The interest in the costume can thus be attributed to an implicit concept of „Großdeutschland“, the desire for identification even far beyond the national borders of that time (and also today). In 1905 the Saltner-figurine became a part of a multi-figure panorama of German traditional costumes in the museum. But 100 years later Jutta Zander-Seidel, curator of the exhibition „Kleiderwechsel“ (that means "change of clothes") at the GNM judged harshly about the former exhibition practice: Neither does the object represent the peasant costume of the past in its historical authenticity, nor does it reach beyond documents of historicized festive culture at that time (cf. Zander-Seidel 2002, p. 76).

From carnival use to cultural appropriation and appreciation

On top of that, the object wasn't even bought in South Tyrol at all, but from a Munich costume fund. The painter Franz Defregger is said to have worn it at a Munich artists' masked ball in 1883 (Ramming 1997, p. 16-18). Was it merely a product of his imagination, made to poke fun at the strangers across the near borders, at those archaic mountain people with their culture, which at the time was perceived as weird, backward, even exotic? There is evidence that Defregger designed costumes too (Irgens 2010, p. 14).

Then it would also be possible that parts of the costume were actually copied, e.g. by using early photographs of Native Americans, perhaps to make the appearance seem even more exotic. The foxtails hanging down on both sides of the face, the necklace of wild animal teeth or the splendor of the feathers come quite close to such cliché images. And Franz Defregger showed great interest in Chief Rocky Bear, for example, whom he met and portrayed in 1890. Rocky Bear had come to Munich (Bavaria) with Buffalo Bills' Wild West Show as a living exhibit (Assmann e.a. 2020, p. 123). But this was seven years after the masked ball. In addition, the object at the GNM is said to have been touched up in the early 20th century, so that it could fit the cliché of the pictorial and written sources of the 19th century even better (Selheim 2005, p. 274).

In the same supposedly colonialist view, Defregger made a painting for an Austrian encyclopedia called „Kronprinzenwerk“ (1885-1902, fig. 5). In this illustration, the figure of the Saltner is used just as clichéd and exoticizing for his country, Tyrol, as we know it, e.g. from images of snake charmers and the Indian subcontinent. But the picture shows a man who looks much like both the Nuremberg specimen – and the artist himself. Could this still be a form of self-exaltation, an act of othering (Said 1985)? If we take into account that Defregger himself was a native Tyrolean, this perspective escapes its chauvinistic dress and shows us a completely opposite form of individual expression and a corresponding search for identification: When abroad, the successful painter dressed like a person of status in his native country.

Fig. 5: Franz Defregger: Ein Saltner bei Meran. 1890, Xylography by M. Kluszewski. © CC-BY-4.0 austria-forum.org

Conclusion

It has taken one century for this change in function to be clearly named in the GNM (cf. Zander-Seidel 2002, p. 148): from an uncertain practical object of use to a product of tourist expectations, from a carnival costume to a decided construction of national identification and back again. The outfit of the vineyard keeper is neither particularly artistic nor valuable. But the questions it is able to generate lead far into a dense field of visual communication across times, national borders and continents, to ideas of foreignness and (self-) exoticization and ultimately to the question of how we deal with them today. The costume of the Saltner and its related outfits seem to come from the supposedly “good old time“. But they illuminate a rather fleeting moment in which historical upheavals in Europe (e.g. early globalization, increased emigration, advanced secularization, consequences of colonialism, desperate search for identity and nation building) are reflected in a peculiar object. They can lead to the question of how to deal with other traditions on the one hand or with the individualization of (male) appearance (e.g. in the later star cult) on the other. The fact that a whimsical hat can still serve an extremely dubious yet visually powerful purpose today was demonstrated by the million-fold shared footage of the self-proclaimed "shaman" storming the Washington Capitol in early 2021.

Special thanks to my students at Gymnasium Wendelstein who enriched this analysis with plenty of valuable questions and discoveries.

References

- Assmann, Peter/Irgens-Defregger, Angelika/Hess, Helmut. 2020. Defregger. Mythos — Missbrauch — Moderne. Innsbruck, München: Hirmer.

- Ramming, Jochen. 1997. Weinberghüter und Heimatwächter. Der ‚Meraner Saltner‘ zwischen Amt und Emblem. In: Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 20. Paderborn. München. Wien. Zürich: Schöningh. p. 116-141.

- Halbritter, Roland. 2005. Saltner – Weinberghüter – Touristenschreck – Vogelscheuche – Papageno – Alpenindianer. „Ihm gebe Kreizer a comprar tabacco; dann still sein gut Freund“. In: Der Schlern, Bozen. August edition 2005, p. 88-104.

- Irgens, Angelika. 2010. Was Tiroler und Indianer im Herzen verbindet, Bayerische Staatszeitung (BSZ). 23.04.2010 (ePaper) and: Unser Bayern 4/2010, München (Verlag Bayerische Staatszeitung)

- von Hörmann, Ludwig. 1872. Die Saltner. In: Der Alpenfreund, Monatshefte für Verbreitung von Alpenkunde unter Jung und Alt in populären Schilderungen aus dem Gesammtgebiet der Alpenwelt und mit praktischen Winken zur genußvollen Bereisung derselben. Dr. Eduard Amthor (ed.), Volume 5, Gera, p. 41-47, proofread for SAGEN.at by Mag. Renate Erhart, august 2005. Spelling carefully reworked and brought up to date: http://www.sagen.at/doku/hoermann_beitraege/saltner.html. Called on 7.02.2021

- Matscher, Hans. 1933. Der Burggräfler in Glaube und Sage. Bozen 1933. Found at sagen.at and carefully reworked by Leoni Wallner. December 2005. http://www.sagen.at/texte/sagen/italien/meran/burggraefler_matscher/wimmetzeit.htm. Called on 7.02.2021.

- Said, Edward. 1985. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Penguin Books.

- Selheim, Claudia. 2005. Die Entdeckung der Tracht um 1900. Die Sammlung Oskar Kling zur ländlichen Kleidung im Germanischen Nationalmuseum. Published by Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg.

- Zander-Seidel, Jutta (ed.). 2002. Kleiderwechsel. Frauen-, Männer- und Kinderkleidung des 18. bis 20. Jahrhunderts (Die Schausammlungen des Germanischen Nationalmuseums). Published by Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg.