A German Perspective on the Akuaba Doll in the Museum Fünf Kontinente Munich

(Download the text in German)

Akuaba Dolls are wooden figures that were and apparently still are in use mainly in rural areas in southern Ghana. Young women hoping for pregnancy or - if they are already pregnant - for the health and beauty of their child, wear these figures on their bodies like real babies and take care of them. That is why they are called 'dolls'.

Akuaba or better Akua-Bà literally means 'child of Akua'. The story tells of "a woman named >Akua< who could not get pregnant and went to a local diviner or priest and commissioned the carving of a small wooden doll. She carried and cared for the doll as if it were her own child, feeding it, bathing it and so on. Soon the people in the village started calling it >Akua< >ba< - meaning >Akuaba's child<, since >ba< means child. She soon became pregnant and her daughter grew up with the doll." (Annor et al., p. 308)

This story also forms the basis for the function of the widespread dolls as aids in a desire for pregnancy. An Akuaba Doll expresses this desire for a child, so the figure is 'cared for' by a girl from puberty onwards. This happens within the family. Outside the family, Akuaba Dolls can be found in shrines under the care of a ritual specialist, where they can be borrowed for their purpose.

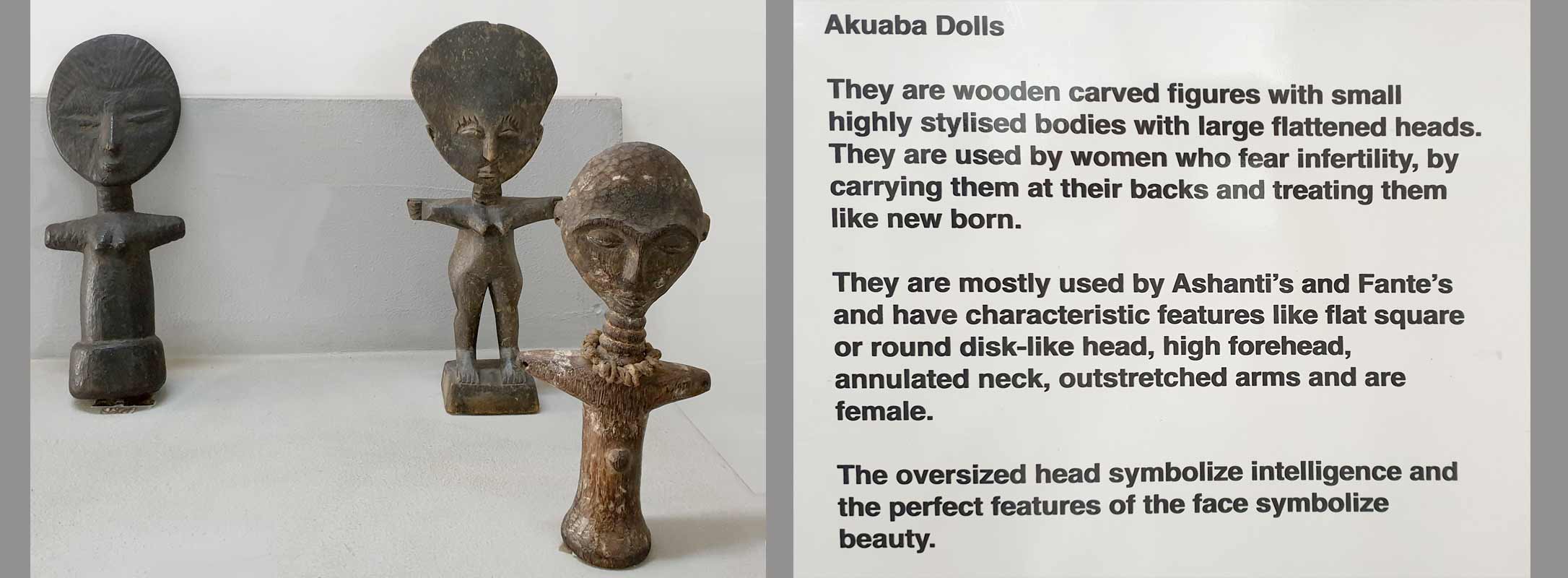

Fig. 1 & Fig. 2 Views of the Akuaba Doll in the Munich Museum Fünf Kontinente

Anonymous artist. Fante Fertility Figure. Early 20th century, Wood. 27,5 cm. Museum Fünf Kontinente. Presentation at Museum Fünf Kontinente.

© Museum Fünf Kontinente

Description

The doll in Munich's Museum Fünf Kontinente (Fig.1) comes from the Fante area. It shows a female figure. The very strongly abstracted forms and proportions symbolise various aspects:

The rectangular shape of the very flat head becomes - seen from the front - somewhat broader in an elegant curve towards the top. A strikingly high forehead, with eyes, eyebrows and nose only indicated, while mouth and ears are missing. The accentuated arch segments of the eyebrows flow together and then form the nose. On the back, the head has geometric patterns (Fig. 2). Added earrings of glass beads give the figure a colourful accent. For Kecskési (p. 38), their daintiness is a sign that the doll has been lovingly treated. At the very top there is another small moulding with a hole where hair was originally attached (compare Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3a: Akuaba Doll from the Linden Museum Stuttgart (Forkl p. 94). Fig. 3b: Use of the doll (drawing by Vanessa Rast - courtesy the artist)

The neck has five rings. It sits on a very slender, round trunk, which in turn stands on a delicate base. Striking are two groups of three diagonal embrasures each, which are repeated on the back. The figure has no arms, the legs are short stumps. The protruding forms in the chest area mark the figure as female. Its strict symmetry is softened by small deviations. One can well imagine taking the cylindrical figure in one's hand.

Material and technique

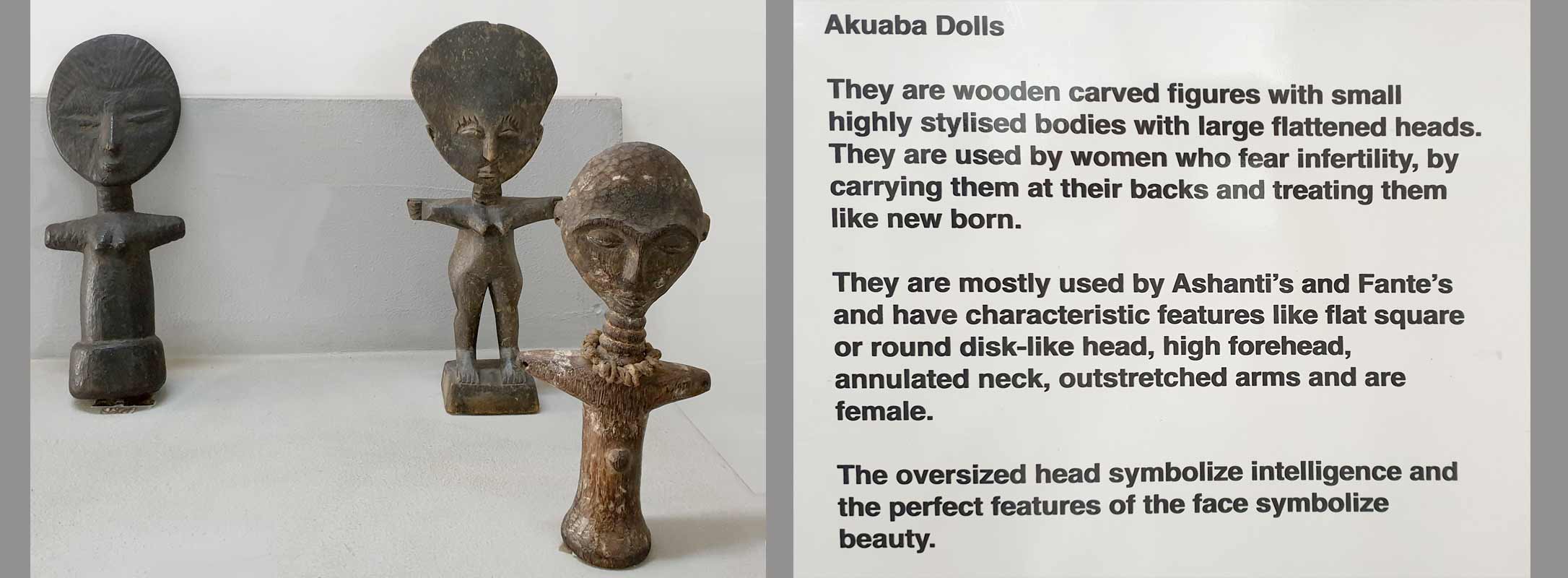

A ritual specialist to whom a woman who wishes to have a child goes makes the decision about the choice of doll at the respective shrine. If no suitable figures are available there, he instructs the woman to order a new Akuaba Doll from the woodcarver. The craftsmen then visit the tree to obtain the wood and ask the tree's spirits for permission to do so (oral information from the Ghanaian colleagues 2022 in Bayreuth [Link]). The Akuaba Doll in the Munich Museum was carved from softwood. (There are also darker examples made of hardwood, for example among the Ashanti, also an Akan group, as the presentation in the Ghana National Museum in Accra shows - see Fig. 4.) In the example in Munich, eyebrows and nose are darker.

Fig. 4: Presentation of Akuaba Dolls at the Ghana National Museum in Accra (March 2023. Photo: the author)

Interpretation of the Munich figure within the original Ghanaian context

(1) Utility function: The figure is made for the family context. It is meant to lead to fertility, sometimes also to the beauty of a child. The size (height 28 cm), the pleasant material and the weight allow the figure to be carried and cared for like a baby. When an Akuaba Doll has fulfilled its task, it is often returned to the ritual specialist who accompanies the process.

The breasts indicate a female figure, which does not necessarily have to do with a corresponding desire for the sex of the child desired. Forkl (p. 94) assumes, however, that "women desire daughters, on the one hand as progenitors in a matrilineality oriented society, and on the other hand as support in household work." (There are also Akuaba figures with the characteristics of both sexes and probably male specimens; furthermore, breastfeeding examples and those who in turn carry other Akuaba Dolls.)

(2) Body shape: T The conspicuous and disproportionately large rectangular head symbolises the head as the seat of intellect and wisdom in local imagery. Akuaba figures among the Ashanti show round heads (see fig. 4), but they are also proportionally very large. High foreheads and flat faces correspond to the ideal of beauty. Luxuriant bulges on the necks tell that the figure is well-fed and thus refer to happiness and prosperity. There are Akuaba Dolls that show more feminine body shapes, wider hips, possibly emphasised by strings of pearls.

(3) The spiritual context: As Nkrumah writes in her contribution, an Akuaba figure serves as a dwelling place for a soul being, a being that is in a transitional area between the earthly and the spiritual world. Carrying and caring for it is a prerequisite for the entrance of such a soul being, which then sets out to appear on earth as a living being, i.e. to enter the family of the young woman through birth. A ritual specialist is involved in the selection, consecration and regulations for use. After a birth, the figure is returned to the ritual specialist.[1]

(4) The social and cultural context: The figure can also be seen as a sign of the traditional expectation for a woman to bring children into the world. In recent times, where traditional societal expectations of women collide with other worldviews, the ritual use of Akuaba Dolls obviously decreases .

Fig. 5: Souvenir shop at Accra Airport (March 2023. Photo: the author)

In the last decades, an interesting production for tourism has been established - apparently the dolls are seen as 'typical for Ghana'. However, these are not Akuaba Dolls in the traditional sense, but rather 'quotes'.

How can one relate Akuaba Dolls to European visual traditions and experiences?

As familiar as the image of an Akuaba figure may seem in Europe - as a 'typical' example of traditional African art - its traditional meaning is unknown in Europe. Nevertheless, it obviously seems to be attractive to tourists, e.g. as 'airport art' (see Fig. 5), perhaps because its shape somehow corresponds to the cliché idea of 'typically African', the size fits well into the suitcase, or the large head (by means of the Bambi effect) makes it appear 'cute'.

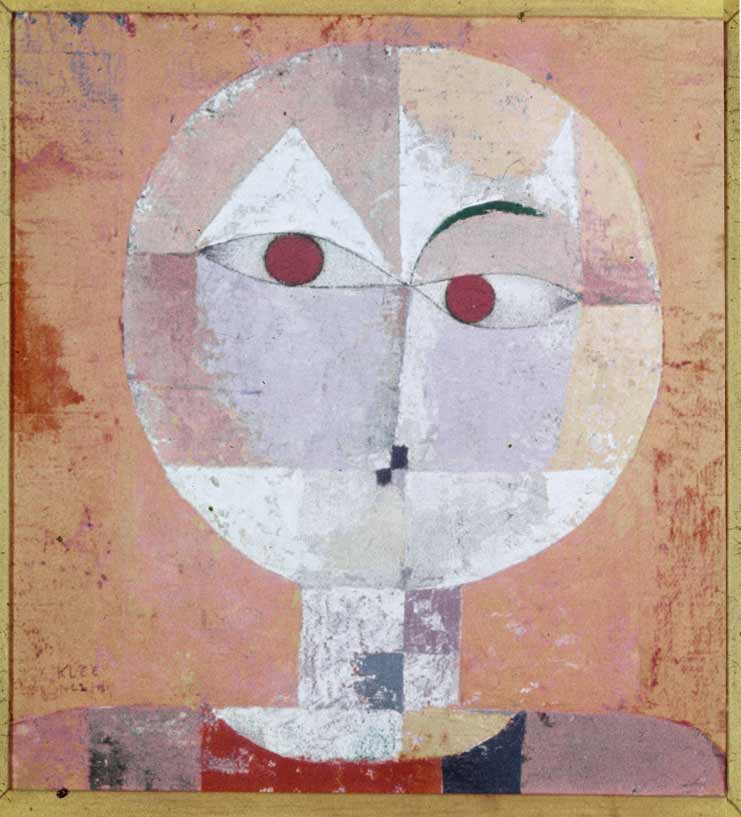

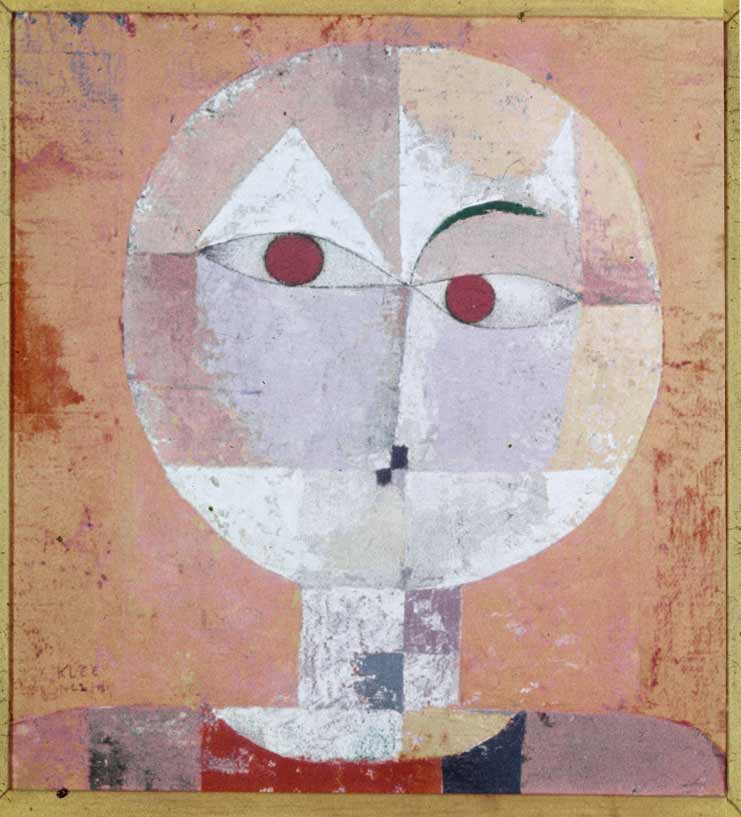

Fig. 6: Paul Klee. Senecio. 1922. Oil on chalk base on gauze on cardboard. 40.3 × 37.4 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel (Wiki Commons)

In the context of art history, the influence of Akuaba Dolls (and many other carved representations from West Africa) on European art of the early 20th century (see Fig. 6) is of interest. [2] The formal similarity to Klee's painting (fig. 6) is striking at first glance, but whether this is a direct reference must first be verified. In the context of art history, it would then be of interest in a next step which aesthetics were of interest to the artists at the time and which they blanked out, i.e. which "image of Africa" they wanted to have and also communicate.

Fig. 7: Hieroglyph Anch

(Photo: https://anthrowiki.at/Anch)

The authors also considered whether the formal similarity of the Akuaba Dolls with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyph ‘Anch’ (the "loop of life" or the "key of life" - see Fig. 7) could have come about through a historical relationship between Egypt and Ghana. This would also correspond to the accentuation of content in Nkrumah's text with regard to the "representation of the woman as the giver of life" (see her chapter). Nevertheless, this association would also have to be examined more closely. To assume a universal archetype in the sense of C. G. Jung appears to be pedagogically misleading in its levelling effect.

In the German educational context, on the other hand, it seems important to link the figure - beyond clarifying its function - to Akua's story and thus include the role of narratives. This prevents another comparison that is also too quick and reductive when it comes to social practices (and not the isolated object), as dolls are also cared for and nurtured in traditional European contexts, but mostly by young children before puberty. So, in Europe, it does not belong to a fertility ritual, even if the child puts itself in the role of a ‘little mother’ or ‘little father’. (Another interesting question, whether Ghanaian women also go to a doctor when they are not pregnant, and whether there are comparable ritualised practices in Central Europe - for example among alternative practitioners or in esoteric circles - would have to be addressed in interdisciplinary approaches.)

Such comparisons appear to be useful, as they can show both similarities and differences, with the aim of better recognising one's own perceptual conventions or stereotypes and thus putting them into perspective. All this still leaves the question of the status of this doll in Munich when it is displayed in a showcase in a European museum (see Lab entry: What is an object? Link). Such a presentation contradicts its ritual and spiritual use. An Akuaba is then no longer an Akuaba. But what is it then?

Sources

This text is based on:

- Contribution by Gertrude Nkrumah: https://explore-vc.org/en/objects/the-akuaba-doll.html

- Talks with the Ghanaian EVC partners in Bayreuth in 2022: https://explore-vc.org/en/activities/archive/april-22-25-2022-joint-workshop-uew-team-and-isb-team.html

- The presentation at the National Museum in Accra, seen in March 2023: Fig. 4.

- Reading: see list of references

References

- Akyeampong, E & Obeng, P. (1995). Spirituality, Gender, and Power in Asante History. The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 28, 3. pp 481-508

- Anderson, Elizabeth L. (1989): The Levels of Meaning of an Ashanti Akua'ba. In: Michigan Academican. 21 205-219

- Annor, I., Dickson, A & Dzidzornu, A. G. (2011): General Knowledge in Art. Accra (Aki-Ola Publications)

- Forkl H. (1997): Healing and body art in Africa. Stuttgart (Lindenmuseum)

- Kecskési, M. (1999): Kunst aus Afrika - Museum für Völkerkunde München. Munich (Prestel)

Footnotes

[1] The number of five neck bulges here (there are also specimens with 3, 8 or 9 bulges) may also be a reference to the sacred number of "Odumankoma", the Akan creator deity, in this context.

[2] On the relationship of the European avant-garde to the aesthetics of West African carvings, see also the discussion of the Blue Rider post on this website (link 1 and 2).