Art and the collective memory of a village

The German sculptor Andreas Kuhnlein (* 1953) has countless solo exhibitions - from Korea to Canada, from Italy to Finland. But his art has its most intense effect in the village where he lives, Unterwössen, population approx. 3500, on the northern edge of the Alps in Germany. Kuhnlein was also born here. His biography - with the stages of carpenter, border guard, farmer, artist - is marked by upheavals. In 1983 he decided to work as a freelance sculptor, and in the second half of the 1990s he developed his own visual language, as a kind of trademark: human figures carved out of wooden trunks with a chainsaw, the surfaces often splintered to the point of abstraction. He often combines several figures into installations, which he constantly rearranges.

Andreas Kuhnlein, The Ship of Fools (detail), wood, life size, exhibition Freising, Photo: Ernst Wagner, 2020

In this context it is interesting that he uses his international recognition and reputation to intervene into his village. This started in the 1990s with exhibitions and events on his small farm, on the edge of the village. Up to 5,000 people came every year, many of them from the village, curious to see what "Anderl" was up to. Since then, some of his jagged wooden figures have stood on the edge of the forest behind the farm, exposed to wind and weather.

Kuhnlein's farm (left) and view from the farm towards the south (right), Photo: Ernst Wagner, 2021

Collaborating with pupils on projects

But he also invites e.g. school classes to his farm to carve. Smaller installations are created here or at their school. Through this, the children become responsible producers. They are proud of their work, and they experience that they can leave their own mark on the site.

Carving action with the pupils of the local school, Photo: Andreas Kuhnlein, 2006

Embellishing the public space

Kuhnlein's approach to designing public space is varied, for example when he carves a large mountaineer for the local sports shop (1992), designs the panels on the maypole (1993), a fountain in front of the town hall (2000), or sets up a large sculpture in the yard of the local school (2001). He also created many works as commissions for private individuals.

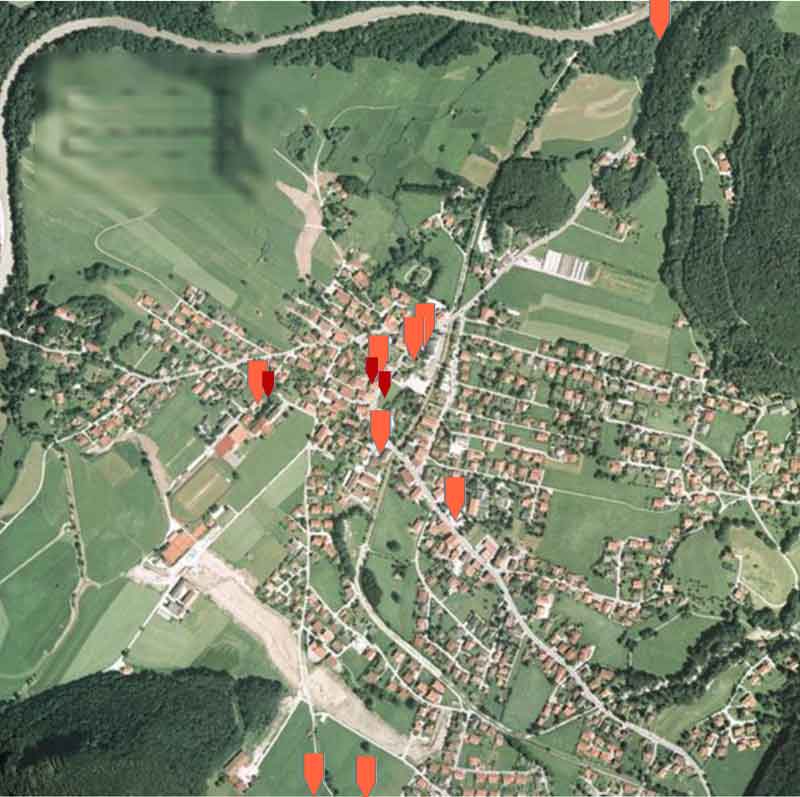

Plan of Kuhnlein’s works in the public space of Unterwössen (dark red: no longer existing), Image: Ernst Wagner, 2021

Interventions

As early as 1999, a third, political dimension can be added to the collaborative actions (e.g. working with children) and the embellishment of the public space. Three examples:

Andreas Kuhnlein, Installation Stillstand, 1999 - 2020, aluminium, H: 9m, W: 5m, Unterwössen, Photo: Andreas Kuhnlein, 2020

Exhortation: Stillstand

There had been a large inn in the middle of the village, which fell victim to a fire. The ruins stood in the heart of the village for two years, after which the large property lay fallow for years - as an "open wound" in the middle of the village. At some point, enough was enough. Kuhnlein welded a huge shovel and pickaxe out of aluminium (H: 9m, W: 5m). Overnight and to the surprise of the residents, he placed it - entitled "Stillstand" - (literally: standstill) on the very plot of land.

Formally, this work shows great similarity to Claes Oldenburg's "Pickaxe", which has been installed on the banks of the Fulda in Kassel for documenta 7 in 1982. Here, too, the alienation of an everyday object by enlarging the scale and changing the material. But Kuhnlein's intervention developed a completely different meaning. What in Oldenburg's case is an ironic gesture, in Kuhnlein's it was a publicly made accusatory reference to the standstill.

After the decision to redevelop the site (now a food supermarket), the installation was removed again by the artist - it had fulfilled its function. In its place, in the same year and on the opposite side of the street, was a smaller wooden figure entitled "Drang nach Oben" (Urge upwards), which has been "observing" the site ever since.

Andreas Kuhnlein, Drang nach Oben, 2007, wood, Unterwössen. Photo: Ernst Wagner, 2021

Remembering: The Refugees' Cross

A second example of such critical interventions is much more modest, almost invisible. During and after the Second World War, many refugees had settled in the village. To preserve the memory of their contribution to village life, especially to the opening of the village community towards diversity, Kuhnlein restored in 2013 - on his own initiative and without payment - the “refugees’ cross” that had existed since 1950 and was slowly weathering away. He also did it against resistance. In this way, he prevented the (often conflictual) period after 1945 from disappearing from the village's memory.

Remembrance and Atonement: Devotional room

The last example of his artistic memory work is about a topic that was taboo in the village for a long time, the abuse of children by a local Catholic priest for years in the 1950s/1960s. Three of Kuhnlein's friends were victims of that priest at the time. Traumatised and without local understanding, two of them became victims of alcoholism. This and the way it was dealt with in the village and by church authorities has occupied Kuhnlein ever since. Lengthy disputes with church authorities followed. Finally, he suggested setting up a place of remembrance for the victims in the village’s church, the very church of the perpetrator, the abuser. For him, a way of coming to terms with the past, for the community to face up to it. Finally, Kuhnlein's idea and design proposal was commissioned and implemented in 2022.

Left: The church of Unterwössen, Photo: Ernst Wagner, 2021 / Right: Andreas Kuhnlein, Devotional room: Working model of the installation, wood, paper, 2021

Andreas Kuhnlein, Devotional room: Woodwork, 2021, wood, Unterwössen. Photo: Ernst Wagner, 2021

The installation is located in a small room directly adjoining the choir of the church, on the base floor of the church tower. The narrow room with unplastered walls, made of rough quarry stones and with two small light openings on the sides, seems both intimate and oppressive. Kuhnlein created three wooden works for the front wall: an abstract resurrected Christ in the centre, flanked by two reliefs. These show in abrupt perspective Christ before Pilate on the right and Christ on the cross on the left: condemnation - sacrificial death – resurrection. In the context of the abuse that is being thematized here, this combination results in an allusive space for thought.

The composition follows late Gothic altars: fully sculptural figure(s) in the centre, narrative reliefs on the wings. The use of the two contrasting pictorial languages also corresponds to this. In the centre, the jagged, abstract, expressive, almost dissolving Christ, typical of Kuhnlein, as a condensed symbol cut out of the trunk with a chainsaw; on the wings the smooth surfaces telling the Christian story of the sacrificial death, now created in conventional carving technique. The contradiction is enormous and remains unreconciled - but united in the triptych. Although small in size, the works appear almost monumental in space.

The inscriptions in the two windows on the left and right allude to the occasion:

Jesus, desecrated and silenced

Many did not want to hear the truth

The victims of abuse have been caused much suffering by the silence of the Church

Lord have mercy

Through this the memory of the abuse inscribes itself as a still open wound - too many victims and contemporary witnesses are still alive - in the space of the church. The resistance to this remembering was great, but the artist's negotiating and assertive power in a process lasting several years were greater in the end.

Conclusion

The role of Kuhnlein's art and his artistic personality in the microcosm of the social space of the village is fascinating. His art is globally oriented but locally focused. It asks questions and answers them in the concrete situation. Decorative: How does the public space of a village organise itself aesthetically? Collaborative: How can space be shaped through co-creation? And finally, related to the interventions: What forms of collective remembering / forgetting / repressing does a community develop and what role can art play in this?

Published December 2021