Ebenezer K. Acquah, University of Education Winneba, Ghana

Unpacking visual narratives from paintings and other pictorial images: perceptions from Winneba

Brief summary of the project

Over the years I have been privy to diverse forms of images, visual culture, and paintings. These include artists’ representations of real world experiences, illustrations from books, as well as representation of visual images from schools or universities. In spite of the enormous body of paintings done by students of the University of Education, Winneba in Ghana, since its establishment in 1992, there seems to be little discourse (with regard to the paintings and other pictorial images) and its related impact among the people living in the area.

This project therefore aims at presenting an analysis of the interpretations of the students’ paintings, from the perspective of the people living within Winneba community. A digital format of the paintings and other pictorial images were viewed and interpreted by a random selection of people living in Winneba. It should be noted that pictorial language practised through pictorial exercises guide one’s attention partly on the content and objective of different pictures and partly on different ways of expressions. As such, an artistic inquiry of visual interpretations in paintings and other pictorial images opens the door for more interaction between the student-artist and the community they live in. Through this project, diverse matters on social issues and visual culture could be further explored.

Pop Visual Culture

Background to the project

What do people see in images or paintings? At a glance one may see a particular object in a picture but a closer look may reveal something different which could be real, surreal, or abstract. And placed within their historical contexts, the details of the paintings or images assume a different dimension and significance.

In an attempt to conceptualize the visuals in the paintings or images, one invariably forms perceptions, opinions, and builds knowledge structures that are bound to accumulate with time. The question is what constitutes a unit of knowledge? In response to this question, one would need to concretize the view of what it means to know. The knowledge formed or acquired should be meaningful and secure a space on which to stand.

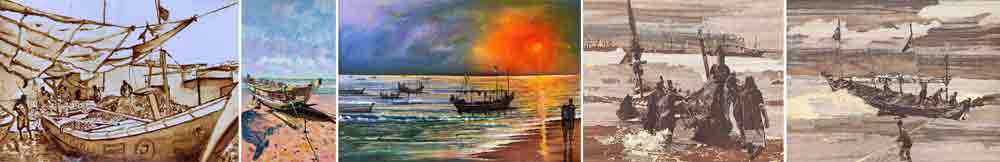

Seascape

How the project was undertaken

The project was defined by the following objectives:

- select people living within the Winneba community to interpret the works based on their perceptions; and

- assemble and organize the paintings and other pictorial images in digital format;

- identify and select paintings and other pictorial images done by students at the University of Education, Winneba;

- analyse the social/educational implications of the project.

Questions to defined the project

The project was guided but not limited to the following questions:

- How would paintings and other pictorial images done by students at the University of Education, Winneba be identified and selected?

- How would the paintings and other pictorial images be assembled and organized in digital format?

- Which group of people living within the Winneba community would be selected to interpret the works?

- What are the social/educational implications of the project?

Methodology

The project was a case study of paintings and other picture-making works done by student-artists at the University of Education, Winneba in Ghana. The paintings were randomly selected by both lecturers and students offering painting as a course in the University. A simple random sampling techniques was also used to select the participants to interpret the works of the student-artists. In all, 20 people constituted the participants for the study (10 student-artists and 10 non-student artists). Data collection instruments were observation, one-on-one interview, and focus group interview. The information from the participants’ interpretation of the works were analysed thematically.

Relevance of the project

The growing interest in scholarly inquiry into visual experiences and studies of seeing and the seen follow an unmistakable social and cultural reality: that images have become an omnipresent and overpowering means of circulating signs, symbols, and information. Many of the everyday iconic events, such as watching movies, window shopping, and television consumption, have become core cultural experiences of urban life in the 21st century.

Interpretations of the works: In Progress

Questions for Participants

QUESTIONS FOR NON-STUDENT-ARTISTS

- What in your opinion is the theme/subject for this work?

- What elements provided you with a hint to your answer?

- How often do student-artists exhibit their works physically within the community?

- How often do the student-artists exhibit their works virtually?

- How is the question of inclusivity/inclusion addressed in the painting or visual?

- How is diversity projected in the paintings or visuals?

- Provide your general comment on the work and its relevance to the social and educational development of people.

QUESTIONS FOR STUDENT-ARTISTS

- What was you motivation for this work?

- What in your opinion is the theme for this work?

- What elements provided you with a hint to your answer?

- How often do you exhibit your works physically within the Winneba community?

- How often do you exhibit your works virtually?

- How is the question of inclusivity/inclusion addressed in your painting or visual?

- How is diversity projected in your painting or visual?

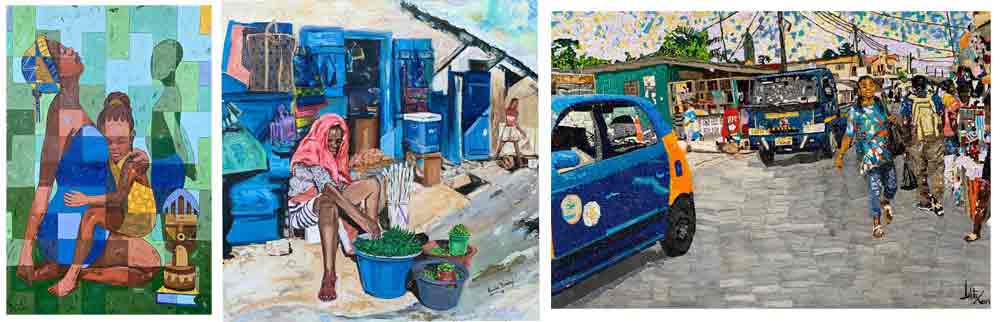

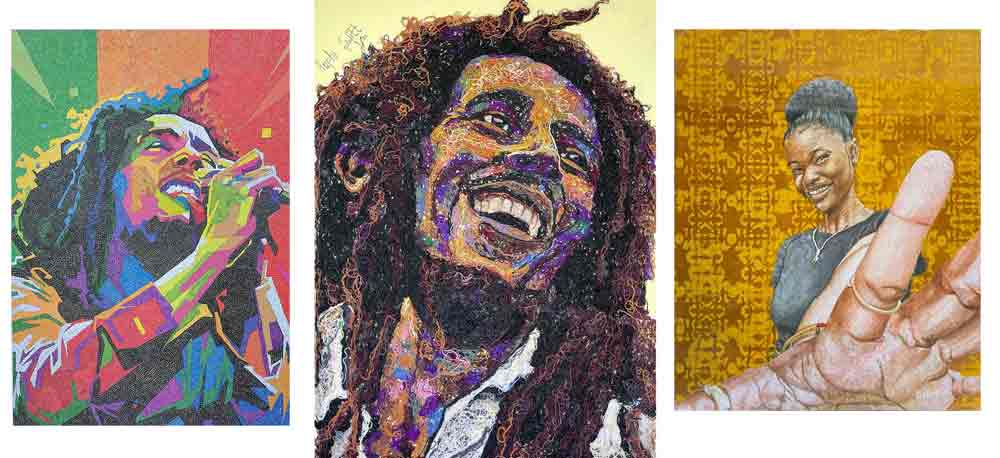

Responses gathered so far indicates that the paintings are categorized in the following groups:

- Seascape and canoes

- Domestic and street life

- Portraiture

- Popular visual culture

Interpretations of the works: In Progress

Reflective comments

I want to argue that recognizing and including visual culture and imagery into the mainstream agenda of art education and educational research would be significant as long as it is not reduced to the repetition of approaches in constrained research projects. The incorporation of visual culture into educational research is not an easy task, and it may challenge art educators with regard to the application of methodology. Such incorporation may also constitute a challenge to the blind spot created by the more traditional ways of seeing and doing research in education, but it is a risk worth taking. If art educators dare to engage in the dynamic process of looking at the field of visual culture using new questioning modes, those areas which have been uncharted and treacherous, they may enter territories that hold layers of reflective meanings and these could be essential for growth and development.

Visual sources of data should be used to advance people’s knowledge about old and new topics in educational research (Fischman, 2014). These sources have the potential of making artistic practice not only more comprehensive and clear, but also politically more relevant because images not only carry information in the constant battle over meaning, but they also (or even fundamentally) mediate power relations.

An analysis of the benefits of interpreting visual culture when groups of people or individuals are engaged in constructing meanings is worthwhile in the promotion of visual culture. According to Barrett (2004), when groups of people are involved in interpreting art, there can be many good results. Significantly, a) it enriches one's knowledge and expand one's experience of the artwork being interpreted from the many points of view of different individual viewers; (b) provides one knowledge of others and how they experience the single work of art differently, (c) enables one to see how one's own ideas and values may be similar and different from others', resulting in self-knowledge. Comprehensive interpretation can provide knowledge of the world and knowledge of the culture in which the work emerged. It facilitates an appreciation of social diversity in the world which, to some extent, depends on what works one chooses to experience, and how one experiences them.